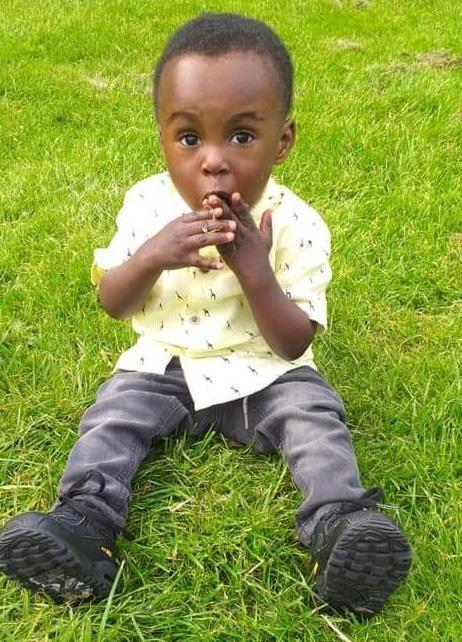

The shocking death of two-year-old Awaab Ishak has been described as a “defining moment” for the housing sector. David Orr argues the tragedy shows the need to fix deep-rooted problems in housing

The whole nation has been profoundly shocked by the news of the death of two-year-old Awaab Ishak as a result of prolonged exposure to mould in his home. The senior coroner, Joanne Kearsley, said in her report it should be seen as a ‘defining moment’ for the housing sector. Housing secretary Michael Gove called it an ‘unacceptable tragedy’. And Lisa Nandy, shadow housing secretary, said ‘Dangerous housing conditions are all too common. Today must mark a step change in the urgency shown towards improving safety and standards.’

They are all right. This was an avoidable tragedy which should never have happened. It comes after a number of other exposes of similarly poor conditions in social housing where damp and mould are all too common and where there are other kinds of disrepair which mean that residents are not safe in their homes.

The first line of responsibility rests squarely and unambiguously with landlords. Those of us, like me, who are involved in the governance or leadership of landlord bodies must take responsibility and be held to account for failings which lead to these extreme housing conditions. There is no excuse for failing residents like this.

But we must also understand that this is not just a fault of landlords but is a deep systemic failure. The truth is that there are hundreds of thousands of homes, poorly designed and inadequately ventilated when they were built 50 or 60 years ago, which are frankly no longer fit for habitation, but are still in use because there are literally no alternatives.

Those of us, like me, who are involved in the governance or leadership of landlord bodies must take responsibility and be held to account for failings which lead to these extreme housing conditions.

Any proposal for significant restructuring or regeneration of failed housing estates may easily take 10 years just to get planning consent, if you can get it at all. It will then take another 10 years for the project to be carried out. From 2010 until very recently there was no government financial support at all for regeneration and no strategy to deliver it.

Not only are many of these homes of very poor quality but they are overcrowded. Such is the pressure on housing, especially for those on low incomes, that many local authorities ask landlords to offer homes to households that are bigger than the homes are designed for. One bed flats for families of three or four people at point of letting. This is always completely unacceptable, but it is also wholly understandable because the demand is so great and the supply of suitable, good quality homes is so small. Serious overcrowding in homes which are old, badly designed, badly insulated and badly ventilated is a recipe for damp and mould. This is not the fault of the people who live in the homes but of a housing system that has comprehensively failed them.

The truth is that there are hundreds of thousands of homes, poorly designed and inadequately ventilated when they were built 50 or 60 years ago, which are frankly no longer fit for habitation, but are still in use because there are literally no alternatives

This is not just a problem in social housing. Damp and mould affect twice as many homes in the private rented sector. And among owner occupiers, although the proportion is lower, there are still hundreds of thousands of homes with damp and mould problems. Indeed, while a shocking 13% of homes in the social sector still fail to meet the decency standard, this rises to 25% in the private sector and 17% for owner occupiers, for whom there is virtually no support and nowhere to go for help.

Michael Gove has called for greater and more effective regulation of landlord services. This is clearly necessary. But where is the equivalent focus on regulation of quality standards in our new and existing homes? As I have argued here previously, the focus on de-regulation and cutting red tape as a numbers game without regard for consequences has directly contributed to the poor quality of some of our new homes as well as the scandal of Grenfell. We must stop thinking of regulation as a problem and understand that it is a necessary function of good governance and high standards. We must define what we want it to achieve, then regulate accordingly.

Then there is investment. We know that the fundamental problem has been our decades long failure to build enough new homes, especially but not only for social rent.

I’m writing this on the day of the autumn statement. One of the charts in the press shows that by far the biggest cut in departmental budgets since 2009/10 has been in housing and communities at a whopping 62.2%. How is this consistent with the scale and challenge of our housing challenges?

>>See also: Orr inspiring: David’s remedy for the housing crisis

The chancellor has announced that social rents will not be allowed to rise next year by more than 7%.

This is understandable and in truth I don’t know of any social landlord planning rises any higher than this. But a rent cut lasts forever.

Cumulatively, this will take billions of investment potential out of the sector, not long after the last rent cut also took billions out.

“We must stop thinking of regulation as a problem and understand that it is a necessary function of good governance and high standards”

This is money that is desperately needed for investment in repairs, renewals and large scale regeneration as well as new build. It comes at a time when 19 of the biggest housing associations have had their viability rating reduced – not because they are failing to manage their resources but because of the huge financial pressures they are already under. And I can’t help but note that there is no similar cap on rents in the private sector where many tenants are under huge pressure.

The calls on the social sector to get its house in order are quite right and must not be ignored. Where there are operational or cultural failings, or where there is any suggestion of racism, we absolutely must improve and deliver. There is, and should be, no hiding place. But if this really is to be a defining moment we must also understand and begin to deal with the systemic failings which lie at the root of so much that is wrong with our housing.

David Orr is chair of ReSI Housing and ReSI Homes, chair of Clarion’s housing association board and former chief executive of the National Housing Federation

No comments yet